2023 Reading Review

I tried to be more precise in how I measured the best books I read this year. For the second year in a row, I’ve been rating each book according to my assessment of its quality and my level of enjoyment. The four best books I read are the ones that have the highest combined rating of quality and enjoyment (I normally pick three, but I had a tie). You can see these on the graphic below.

- Rebecca

An immensely compelling book despite the fact that none of the characters were particularly attractive. The unnamed protagonist is particularly irritating in her total passivity. She joins Tess Derbyfield and Silas Marner in an unholy trinity of protagonists who are exclusively acted upon. It can be an effective tool though in the hands of a skillful author; the reader feels as powerless as the protagonist as her inaction slips her deeper and deeper into ruin.

- Mystic Masseur

A quick, funny book that reads a lot like some of Herman Charles Bosman’s best work. It is Naipaul’s first book, and far more light-hearted than his later books, but no complaints there. I think part of the reason I was so interested by the book is that I saw some of myself in the protagonist. That always makes one more interested in the action and outcomes.

- The Greeks

This is an unusual history of the Greeks in that it does not merely focus on their glory period. Instead, we examine classical Greece, Roman Greece, Byzantine Greece, Ottoman Greece, and finally modern Greece. My family have been having a recurring debate Greece’s contribution to Western civilization, and whether that has been overstated. I tend to think their impact has been understated, if anything. So, I had this question on my mind as I read this book. The author only deals with this tangentially; nevertheless I found plenty in it to show the impact they had on Western civilization. Consider the following Greek contributions as detailed in the book:

Politics (p.76-80, 116-120, 130-136, 140-147, 151, 228). They were the first political entrepreneurs if you will; the first to think seriously about what government ought to do (as well as inventing many forms of government like democracy). As part of that, they were the first to write popular constitutions, or constitutions based on the will or input of the general citizenry. These constitutions included values we now hold sacrosanct, like equality under the law for all individuals. Indeed, more than anyone else, the Greeks were the first to elevate the individual to its preeminent position in society, an orientation we derive from them.

We also have inherited the concept of political autonomy, freedom, and patriotism that they were the first to articulate and to fight for. A patriotism rooted not in defense of religion or tribe but in defense of a shared set of cultural and intellectual values. This is a conception of identity we still use today; what is it to be Western if not to share a belief in the primacy of certain values.

Less attractively, they were also the first to articulate the political philosophy we attribute to Machiavelli, i.e. Machiavellian or using Real Politik. The Athenians justify their rule over other Greeks by saying:

“We have done nothing surprising or contrary to human nature in accepting rule over others…and refusing to give it up, under the domination of the three most powerful motives–prestige, fear, and self interest…It has always been the way of the world that the weaker is kept down by the stronger.”

Science and Philosophy (p.97, 116, 127, 149, 175, 194). Although other cultures practiced applied science and philosophy, it was the Greeks who systematized these disciplines and formalized the rules we associate with them (logic, inductive versus deductive reasoning, experimentation, rhetoric, moral philosophy and ethics, conditions of knowledge, and so on). It’s not hyperbole to say the Greeks invented reason, as sure a cornerstone of Western civilization as anything else. Furthermore, the Greeks were the first historians; the first who tried to write objective histories based on eyewitness accounts and to weigh and analyze disputing narratives.

Art (p.114-123, 148). The Greeks bequeathed us epic verse, Drama, tragedy, comedy, and political satire. They also gave us (or at least articulated) the conception of idealism, nostalgia, and catharsis we understand today. They also gave us the idea of popular artists, writers, and playwrights catering to a reading or viewing public willing to pay money to consume that art.

Religion (p.92 & 241). The Greeks, unlike their contemporaries, were the first to recast their gods in their own image, an anthropomorphizing tendency we continue today. The author makes the point that Christianity is a reconciliation of Greek thought with the teachings of Christ.

Again, this is not a thesis the author takes up in the book, but there is enough here to show their tremendous impact on Western civilization. I agree with John Stuart Mill:

“The true ancestors of the European nations are not those from whose blood they are sprung, but those from whom they derive the richest portion of their inheritance. The battle of Marathon even as an event in English history is more important than the battle of Hastings” (as quoted on p.113).

- Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance

A challenging book, and much of it over my head, but one worth thinking about. After finishing it, I checked some reviews online and saw that it’s not taken particularly seriously by professional philosophers, but that’s okay–I’m not a philosopher, and I see a lot to value here. Or at least I think I do. It’s quite difficult to put the main thesis into a short and concise summary, but I’ll give it a shot. The premise of the book comes from the narrator’s inability to understand his friend’s lack of interest in motorcycle maintenance. His friend, he decides, sees only the aesthetic appeal of riding motorcycles without sensing the beauty of the mechanical and chemical processes that make that riding possible. He thinks this is emblematic of a deeper divide between two modes of experiencing reality, which he terms “classical” and “romantic.” He seems to use these definitions as he pleases throughout the book, but ostensibly a classical way of seeing the world is seeing the forms and systems of how things work, and one which is based on rational principles. A romantic way of viewing the world, in contrast, is more based on appearances, aesthetical value and emotions; it is based not on reason but on intuition.

He lays the blame of this divide (which he doesn’t think is an inevitable or essential one) at the feet of Greek philosophy, saying they created these lines of demarcation, creating the two approaches that always seem to butt up against one another. This wasn’t a problem in their era, but it is in ours. The triumph of the classical or rational-based approach has led to an ugly, mass-produced, world that meets our immediate needs without providing for our spiritual ones. That’s why people are longing for mystical or “authentic” experiences; they live in a classical world that is inadequate to give them “what they know is real experience” (p.170). The author here is essentially anticipating Inglehart’s work on material and post-material values. That is, that great wealth in Western societies has led these societies to place a greater emphasis on values not associated with immediate needs. Instead we place a greater emphasis on more abstract principles such as social justice, equity, equality, environmentalism, and so forth. Or to use another example, Inglehart would say previously we valued employment for the sake of survival, but now we value employment (or say we do) for the sake of what we can do in the world to make a positive difference, or for its capacity to provide some sort of fulfillment to our own lives.

The narrator does not leave his argument there, however. He thinks the solution to bridging this divide, a divide which does not have to exist in the first place, is to use the concept of quality. This is where things get difficult. It is hard to define quality as the narrator means it. Not only does he seem to use the word to mean different things in different contexts, but he also thinks it is by nature indefinable. Or even that defining it will kill it. Quality is so immense that the minute you define it, you are defining something less than quality itself. He references Lao Tzu here: “the Tao [way] that can be described is not the eternal way, and the name that can be named is not the eternal name”; insisting on a definition of something that is by its nature incapable of definition will not give you eternal truth. It’ll just give you your limited and flawed definition or outline of it.1

The best attempt he gives us in the way of defining is that “quality is a characteristic you recognize by a non-thinking process, but which is otherwise indefinable” (p.207). You cannot define it, but it exists. It exists because we can clearly see some things as better than others, which means that some things have a higher quality. The example he gives is writing; in grading student essays, some are just better than others, and everyone can sense that even if it is sometimes difficult to point out what makes Essay A better than B. It just is.

He recognizes that quality may seem subjective (two people can obviously disagree about if one thing is better than another), but seems to state that it is objective too, in that disagreement about quality stems from different cultures and backgrounds emphasizing different things. He posits that if two people were raised the same way and had the same experiences, they would always agree on quality. That doesn’t sound right to me, especially given the random luck of genetics.

The narrator thinks we should think of quality as coming before rationality, before even subject or object. He says that quality is not a thing, per se, it is an event; the event where subject becomes aware of objects. But the existence of subject and object is deduced from quality itself; this is the first cause. To see any shapes and forms in the universe is to intellectualize; quality is independent from these shapes and forms but is instead the way we pre-select if and how we see them. In life on Earth, this is manifest simply in the response of an organism to its environment. If you put a drop of acid in an amoeba’s dish, it will flee the acid to a less contaminated part of the dish. Why? Because it seeks better quality for its life. Likewise, we constantly want better quality conditions (materially, intellectually, and spiritually).

So how does quality solve the divide between classical and romantic approaches? The narrator thinks that this comes from understanding that quality proceeds rationalism, but also from deliberate pursuit of quality itself. We should seek quality in everything, which means making things with care, doing things with care, and acting with care. The soullessness of modern life comes from everything being done and made without care. Our lives are filled with cheap, convenient, mass-produced products, pursuits, and employment. Lack of quality in our lives makes us feel like meaningless cogs; going from a mass-produced home to a mass-produced office building on a mass-produced freeway in a mass-produced car to work in a job we only do to afford the mass-produced lifestyle forced upon us. After our shift doing whatever tedious work we are forced to do, we return home and spend our last precious hours watching lousy mass-produced television (or nowadays, scrolling endlessly through content suggested by a mass-produced algorithm). Recognizing this soullessness, our society gives us things that seem to embody better quality but ultimately don’t. A fancier mass-produced refrigerator, alternative music that is ostensibly rebellious to this mass-produced system but really is made for the same reason (money instead of pursuit of quality). No wonder, says the narrator, everyone is lonely and depressed. We need quality in our lives. We can do this by self-consciously trying to exercise quality in all we do, in our work, our relationships, everything. The world wouldn’t be soulless if every action was undertaken with quality as its soul motivation, rather than money or some other less satisfying motivation.

A lot there, although I will say that the philosophy is only part of the appeal of this book; it’s eminently readable in terms of plot and character too. It also plumbs much darker and more emotional depths than one would consider with a book like this.

Now on to the stats!

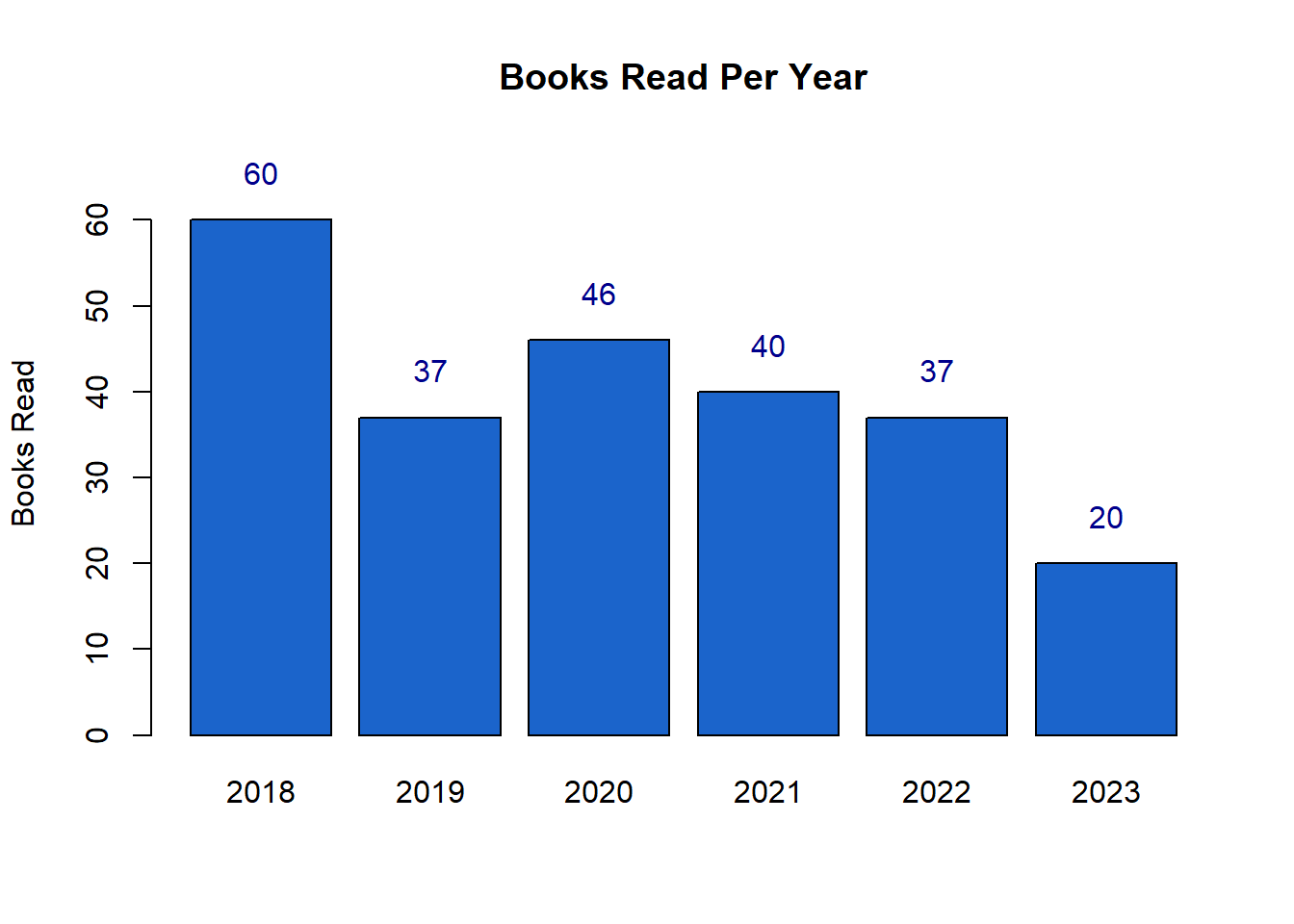

The precipitous decline this year I attribute to the Wheel of Time. I decided to re-read the series, but given its length, to only read from the point of view of the narrators I care about. So I didn’t actually read them per se, but the skimming still took literal months.

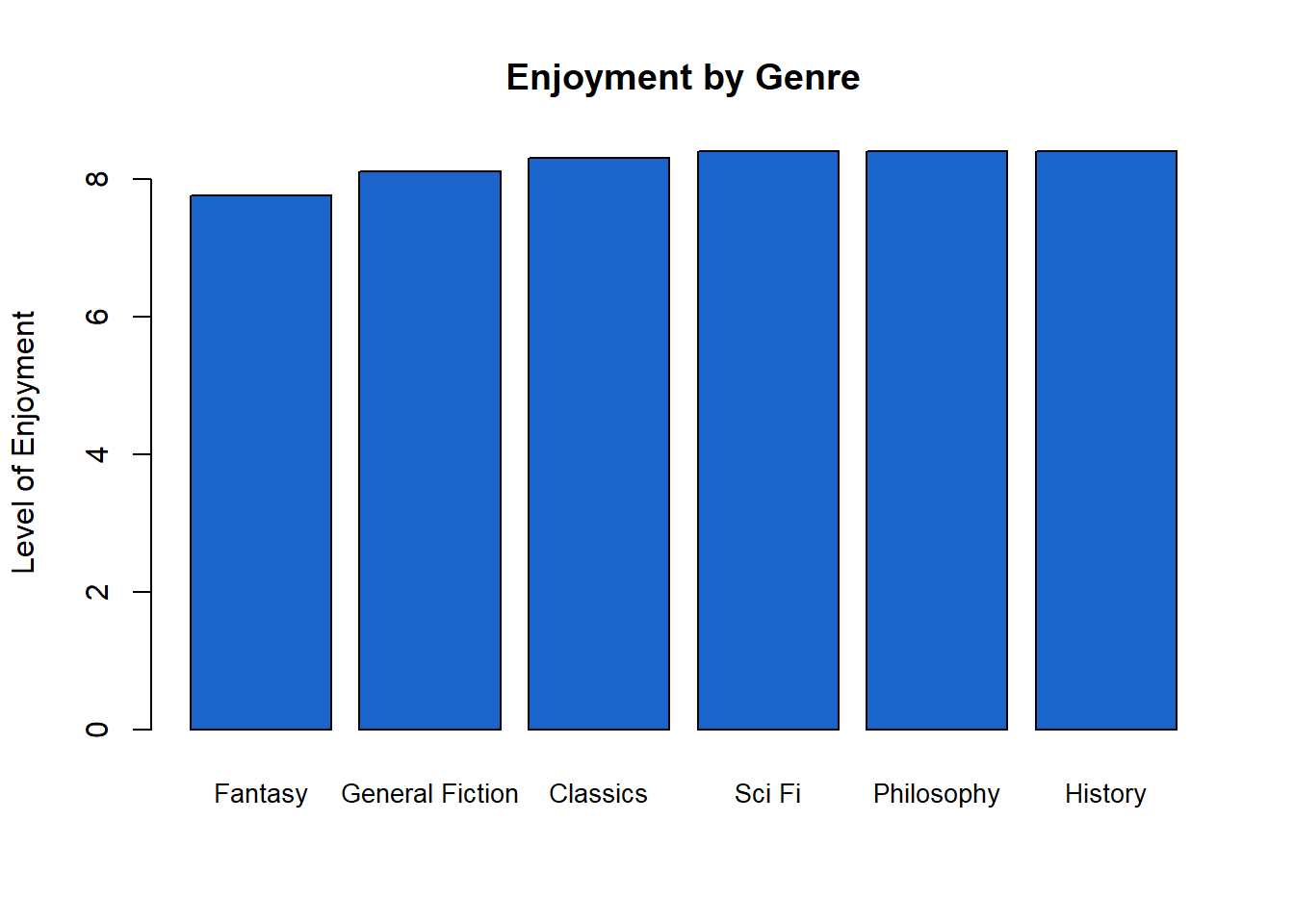

The thing I like about keeping track of my enjoyment is to see if I can figure out which types of books I enjoy. Below I consider author gender, author nationality, year of publication, and genre to see if any preferences emerge.

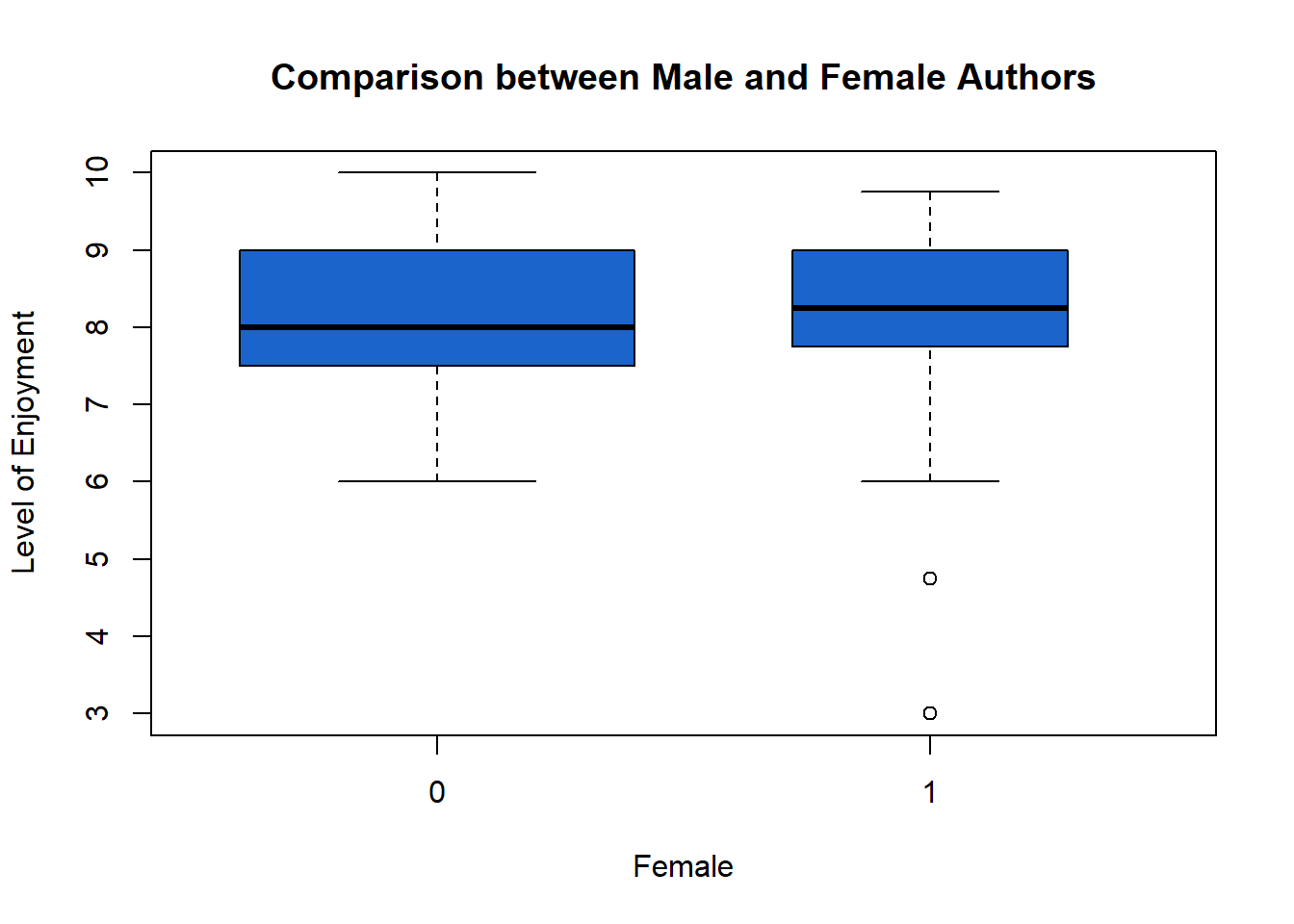

No real difference although the boxplot shows that the range of scores I give to female authors is more consistent and tightly distributed. There are also fewer female authors to evaluate in my dataset of read authors, as indicated by the comparable sizes of the boxes, a nice added feature in R I like.2

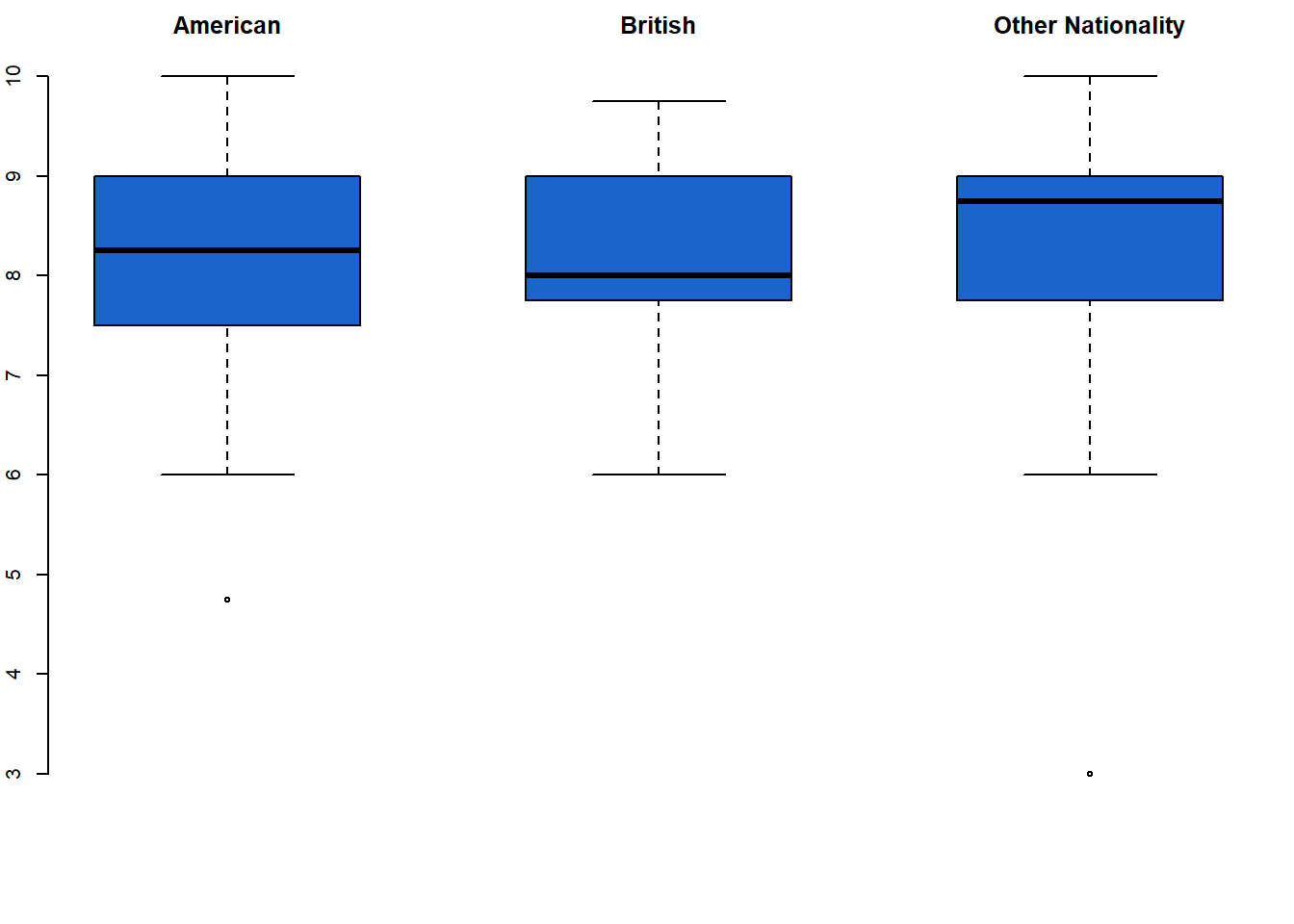

Fairly similar in terms of author nationality, although British authors have the lowest median score, and authors who are neither British nor American score the highest of all. Makes sense; if I’m going to read foreign literature it’ll likely be the absolute best, whereas I’ll settle for any old American or British garbagy fantasy novel.

Fairly similar in terms of author nationality, although British authors have the lowest median score, and authors who are neither British nor American score the highest of all. Makes sense; if I’m going to read foreign literature it’ll likely be the absolute best, whereas I’ll settle for any old American or British garbagy fantasy novel.

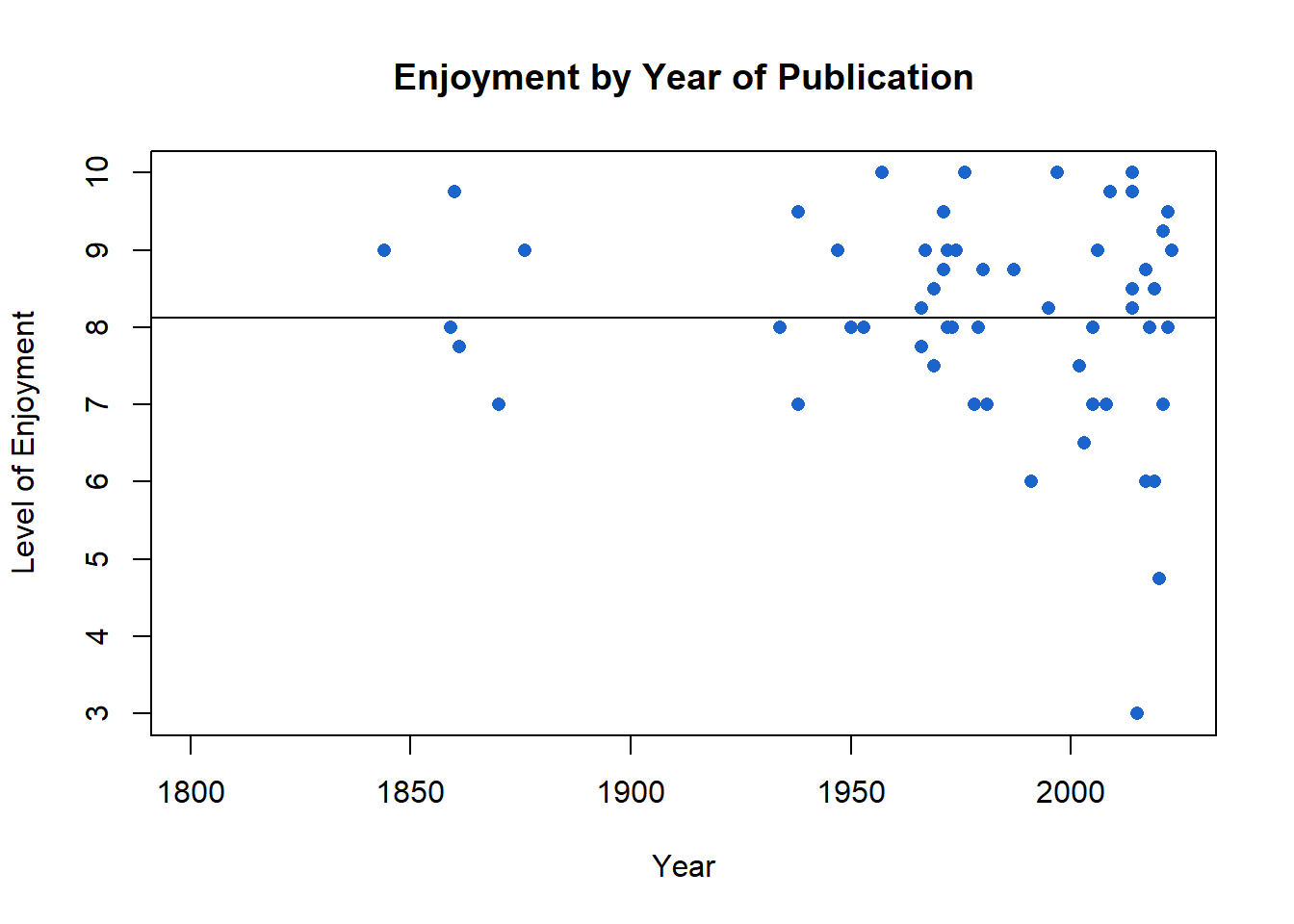

Essentially no relationship between year of publication and my self-rating of enjoyment. I marginally enjoy older books though.3

No one genre stands out in terms of enjoyment from the books I read; I enjoy each of these genres about the same. So all in all, the evidence suggests I’m a pretty undiscriminating reader when it comes to these categories.

And to end, a list of the books I read this year (in order of reading) and how much I enjoyed each one:

| Title | Author | Level of Enjoyment |

|---|---|---|

| The Silver Chair | C.S. Lewis | 8.00 |

| Blinding Light | Paul Theroux | 7.00 |

| Rocannon’s World | Ursula Le Guin | 7.75 |

| City of Bones | Martha Wells | 8.25 |

| Planet of Exile | Ursula Le Guin | 8.25 |

| City of Illusions | Ursula Le Guin | 9.00 |

| The Enigma of Arrival | V.S. Naipaul | 8.75 |

| A Bend in the River | V.S. Naipaul | 8.00 |

| City of Brass | S.A. Chakraborty | 8.75 |

| Kingdom of Copper | S.A. Chakraborty | 8.50 |

| Empire of Gold | S.A. Chakraborty | 4.75 |

| Mystic Masseur | V.S. Naipaul | 10.00 |

| Daniel Deronda | George Eliot | 9.00 |

| Slaughterhouse 5 | Kurt Vonnegut | 8.50 |

| Rebecca | Daphne Du Maurier | 9.50 |

| Inside the Jihad | Omar Nasri | 9.00 |

| The Cats of Ain Soltaine | Bethan Owen | 9.00 |

| Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance | Robert Pirsig | 9.00 |

| The Portable Plato | Plato | 7.75 |

| The Greeks | Roderick Beaton | 9.25 |

I often think about this concept in my own faith. Latter-day Saints are sometimes guilty of glibly reducing the entirety of existence to a handful of arrows and labeled bubbles called the Plan of Salvation, and seem to have full confidence that the nature of existence has been more or less figured out as a result.↩︎

I love boxplots. If you’re not familiar with them, I asked Chat-GPT to write up a quick description of what they do: “A boxplot, also known as a box-and-whisker plot, provides a visual summary of the distribution of a dataset. It displays key statistical measures, including the median, quartiles, and potential outliers. The plot consists of a rectangular”box” that represents the interquartile range (IQR) between the first and third quartiles, with a line inside marking the median. “Whiskers” extend from the box to the minimum and maximum values within a certain range, and any data points beyond the whiskers are considered potential outliers. Boxplots are useful for comparing the central tendency and spread of different datasets or identifying the presence of outliers.”↩︎

Just by way of explanation, the scatter plots I’m showing comes with a regression line plotted using a basic bivariate ordinary least squares regression. That line is a line of best fit; it tries to predict the relationship between the two variables (shown on the Y and X axes). I’m not going to be tedious and present the regression table (this is for fun!), but you can just eyeball the relationships or simply look at the regression line. A negative relationship will be shown as the line sloping down from left to right, and a positive relationship will slope up from left to right. The steeper the slope, the more correlated the variables. In the case of the scatter plot above, the modest slope indicates that the two variables are not well-correlated.↩︎