2020 Reading Review

Contents

2020 may have been a bad year in general, but it was a pretty good year for reading. Books are pandemic-proof. And so, without further ado, I present my much-too-serious review of my year’s reading. Another step in my journey of quantifying every aspect of my life. Next year I’ve got to remember to track my television and movie consumption.

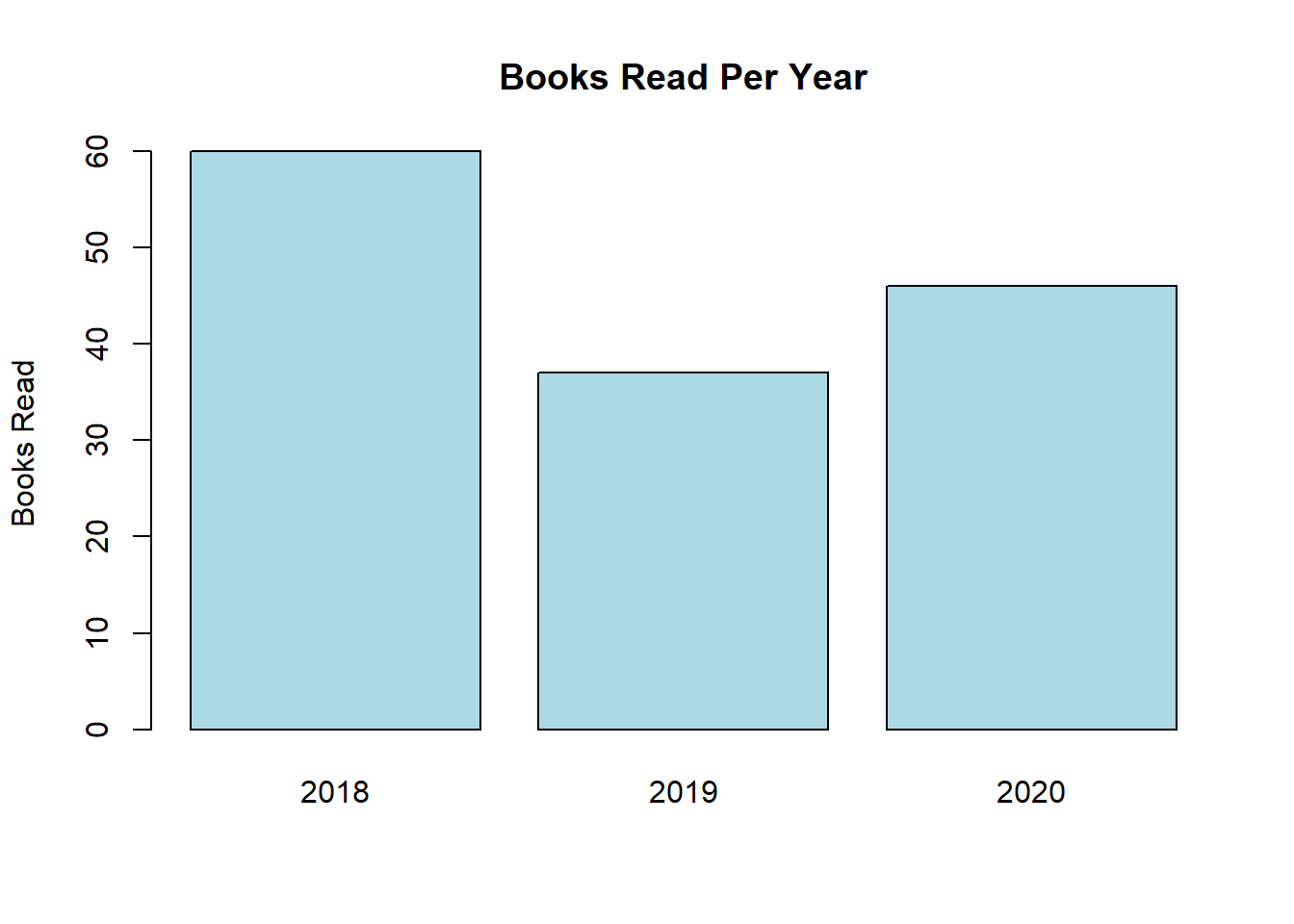

At least I read more than last year anyway. Nothing will ever touch my last year in the Peace Corps though (2018)–so much free time for reading. I only have 3 years of data, but I suspect 2018 was a bit of a situational outlier.

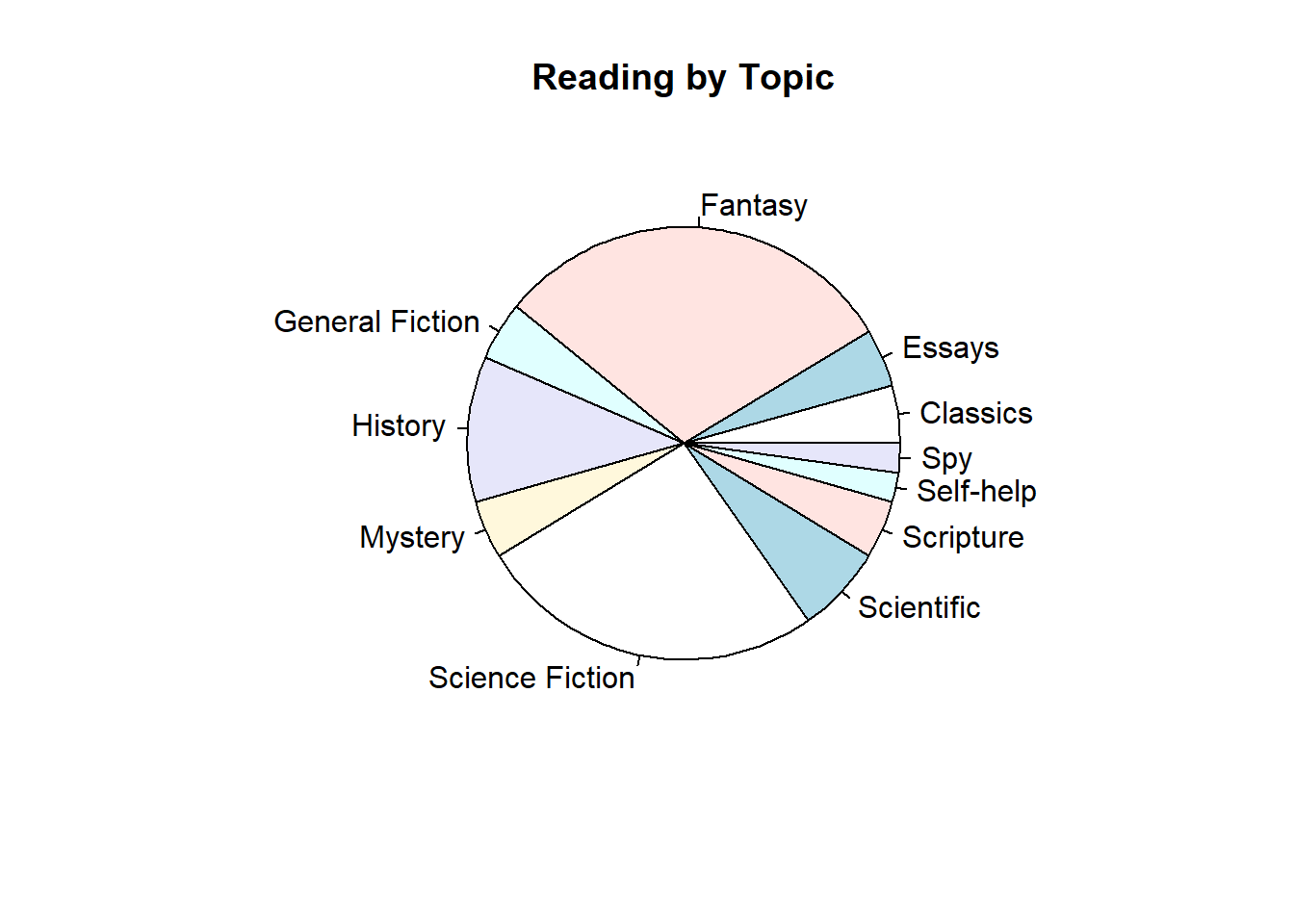

As per usual, my go-to genres remain science fiction and fantasy.

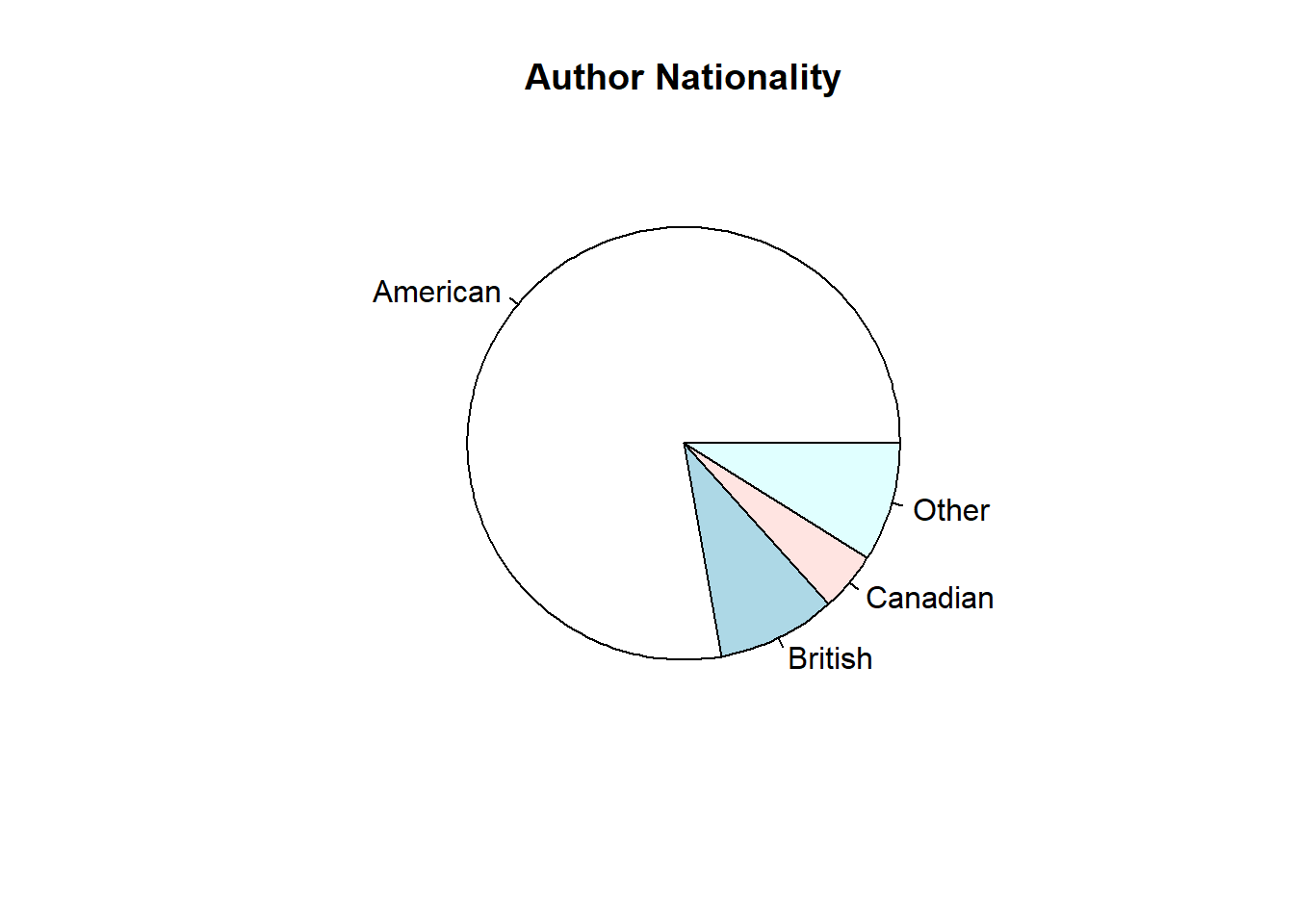

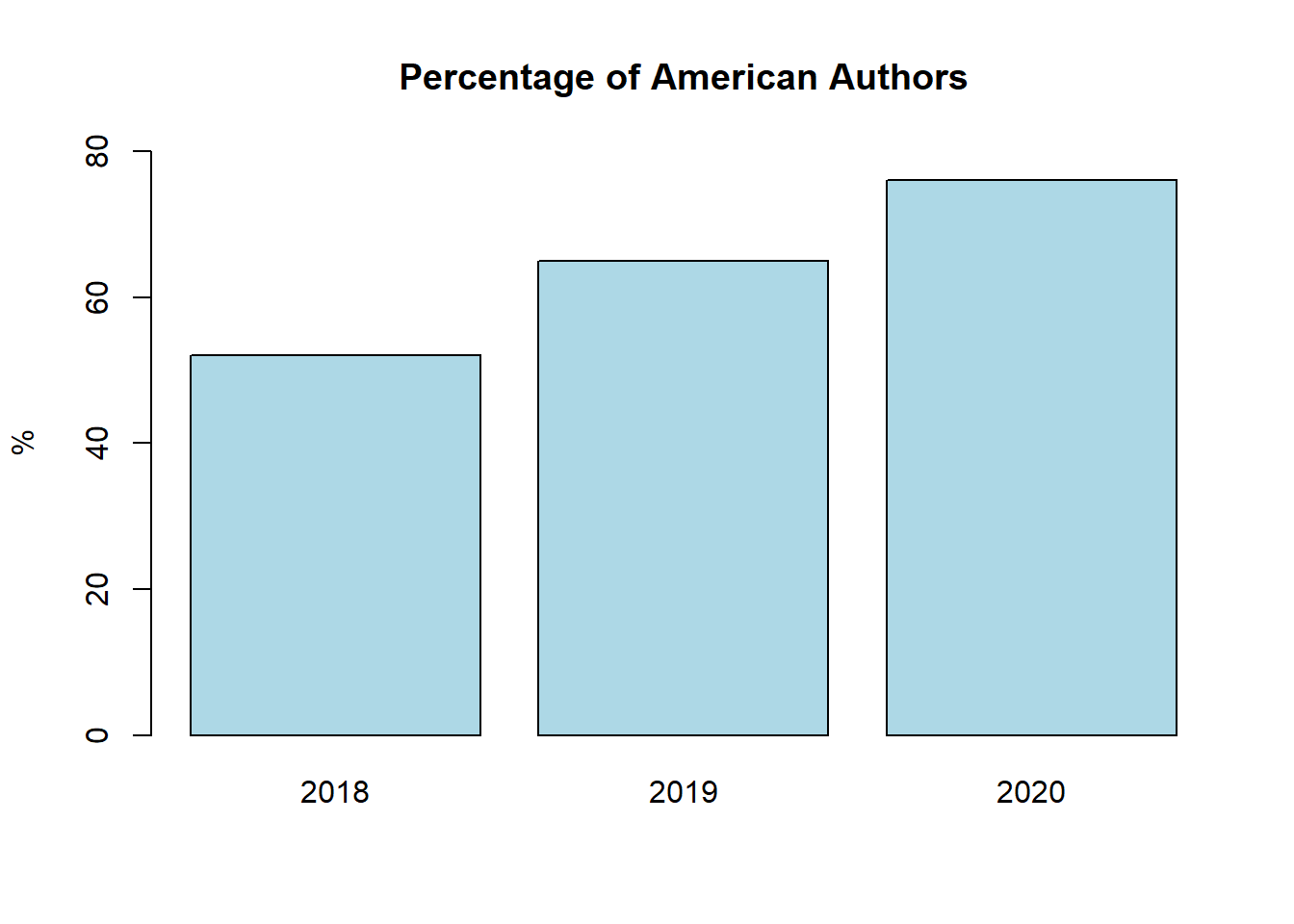

A little more surprising to me was how skewed my reading was towards Americans. 76% percent of all my books had American authors. This seems to be becoming a trend.

Perhaps I am becoming even more American over time and my reading is reflecting that?

Some other stats from my books this year:

28% were non-fiction

41% of the authors were female

2000 was the median year of publication

407 pages was the average length

33% were re-reads.

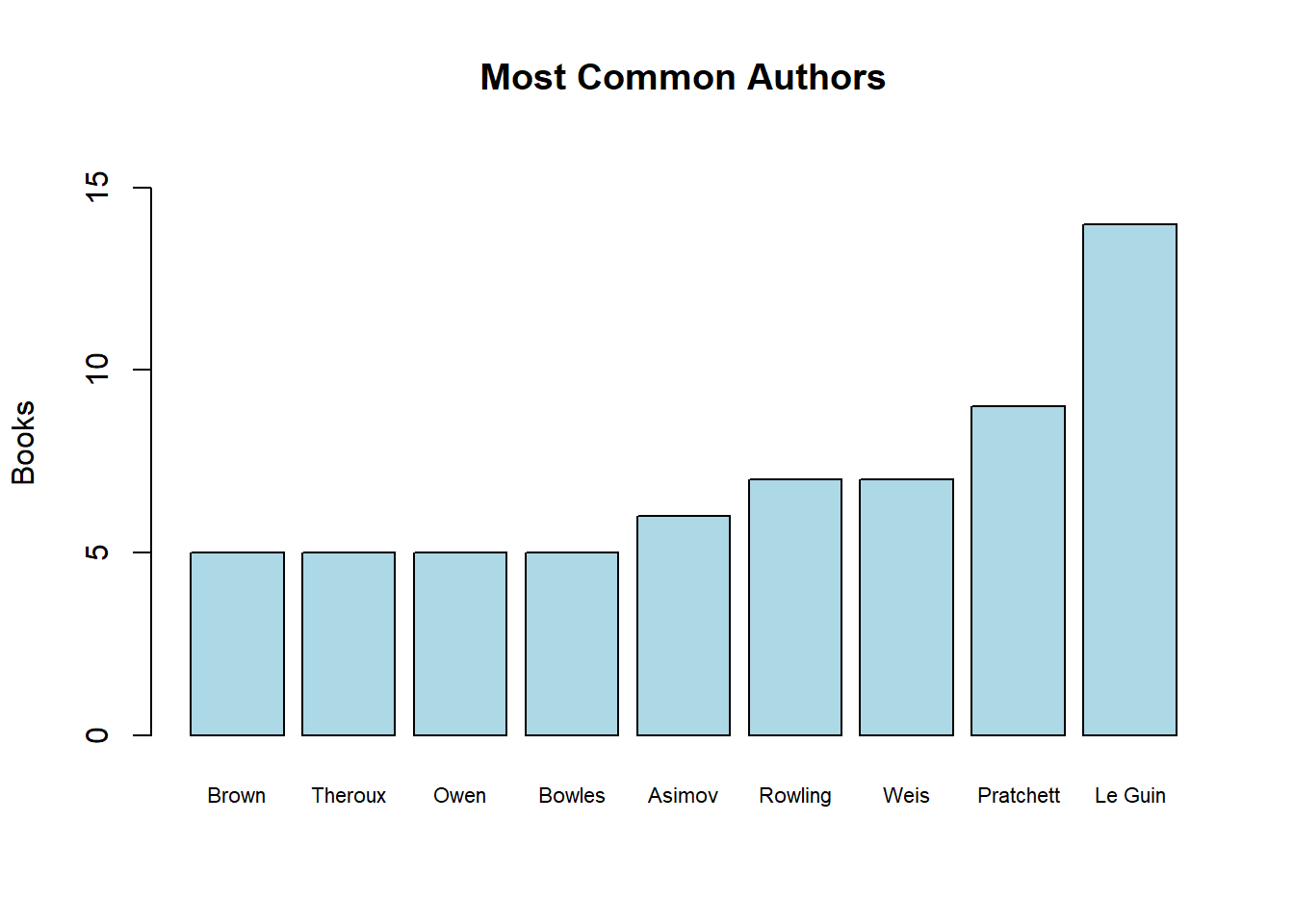

Now that I have 3 years of data I can start looking at some comparisons between years. For example, which authors have I read the most over the last 3 years?

Ursula Le Guin is my most read author of the past 3 years, followed by Terry Pratchett. The top 5 are all fantasy and science fiction authors. The only 2 “serious” authors on the list are the two Pauls: Theroux and Bowles.

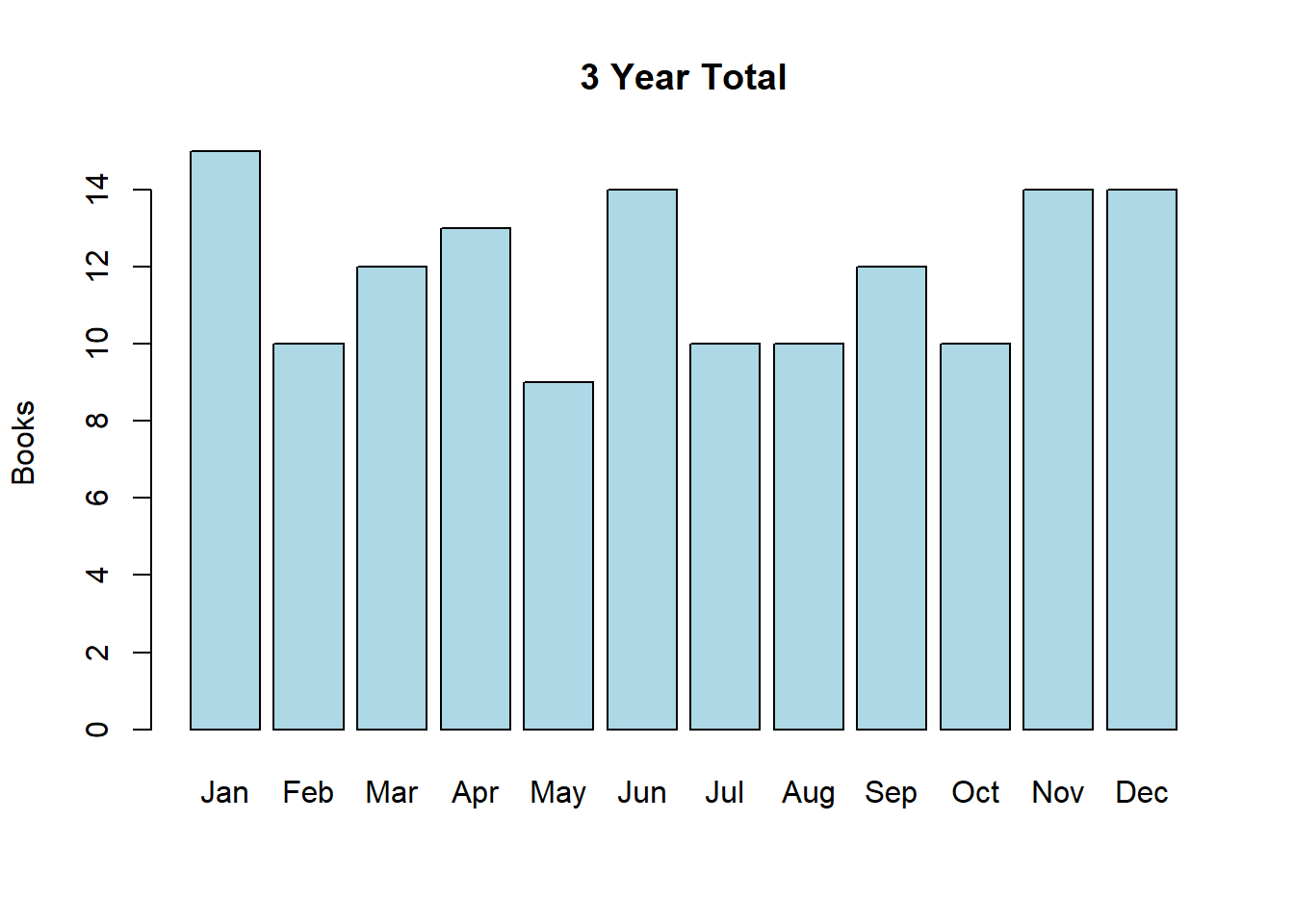

I can also see when I read. Comparing the months of the year over the past 3 years:

On average I read 5 more books in January than I do in May. Could it be that those are the months with the best and worst weather? It seems like that might be a factor when you consider 3 of the 4 highest reading months are November, December, and January; and 3 of the 4 lowest months are May, July, and August. Overall though my reading is pretty consistent throughout the year; I only read about a book extra per month during cold weather months.

My 3 favourite books I read in 2020:

- The Lower River

Paul Theroux is one of my favourite writers. His prose is refreshingly clear and plain, and his perceptiveness impressive. More than any other writer I know, he also exemplifies the maxim: “Write what you know.” What he knows is travel, Africa, the complexity of families, and apparently loneliness, disappointment, and a sense of failure. All of his work is filled with these themes and that makes them read true. I find it much more rewarding to read truth, even in fiction. In this book, Theroux’s truth is the disappointment an old Peace Corps Volunteer faces when returning to his site decades later. It is also filled with his thoughts on Africa, Africans, foreign aid, and the nature of evil. If it sounds oppressive–it is. He leverages his years spent in Africa to create an incredibly vivid sense of place–of the heat, the closeness, and the despair he feels in central Africa; a place he regarded as Eden. Indeed, allusions to the Garden of Eden are plentiful–the narrator has a penchant for snakes. Theroux leaves it up to the reader to decide who plays Lucifer in the suffocating African bush

2.The Little Stranger

A bit of a departure for me; this was a book that Bethan recommended (as was the Lower River actually). I don’t typically read mystery novels; in fact, I can only recall a couple of P.D. James books as being the others I have read. Like Theroux, Waters writes expertly. The pacing is slow and the content sometimes repetitive, but that brilliantly mirrors the general mood of the protagonist–a country doctor who feels adrift and alone in a quiet English town.

- The Rise of Christianity

In the last year I have become a little more conversant in the sociological literature of religion. This book fits squarely into that category although it is written for a more general audience. It provides a fascinating glimpse into the Roman world that served as the nursery for the early Christians. The author’s main thesis seems to be that the rapid growth of Christianity can be explained fairly simply using sociological theory, but that does not make it any less miraculous. It is also a useful reminder of how radical early Christians were in comparison to the society in which they lived. We are starting to see a reemergence of that divergence once again.

And to end, a list of every book I read this year in order of completion.