In a previous essay, I speculated on the effect of media on citizens. In this essay, I extend that

discussion to consider how social interaction is intertwined with media effects. Furthermore,

since reasonable communication and deliberation are norms we associate with republican or

deliberative democracy, I also examine how social interaction among citizens affects our views

on democracy.

Social Interaction as a Political Phenomenon

In order to navigate the political world and make decisions that benefit them, human

beings need to be able to learn about politics. They can either do this themselves through

experience, or rely upon the knowledge others are ready to impart (Lupia & McCubbins, 1998).

This knowledge can come from political elites, the media, or (as is the focus of this paper) one’s

social network. Since human beings are cognitive misers, they want to learn the information

they need with the least effort possible (see chapter 2 of Lupia & McCubbins, 1998). One’s

social network, therefore, represents an easy means of acquiring political information with little

costly effort (Carlson, , 2019, p.325). Someone else has already done the hard part (i.e. reading

about political events); you can just benefit from their efforts. This represents the rational citizen

that Anthony Downs would approve of, and would appear to be only a theoretical construct of a

citizen, but for focus group work that has revealed that people do indeed profess to talk about

politics in order to gain information as well as persuade others (see Walsh, 2004, chapter 3).

Whenever we communicate socially there is always the intervening effect of social

identities to consider. Cathy Kramer (referred to in the citations for this paper as Walsh, 2004)

and her study of the “old timers” provide most of the work here. Kramer found that when

discussing things in social groups, participants repeatedly use collective identities in how they

frame issues (p.10). Their social identities are also a key part in how they evaluate issues.

Kramer gives a good account of this process and how it operates on p.19. She explains that

through social interaction, people evaluate themselves in comparison with the other individuals

in the group and the norms they display. This gives them an idea of what they perceive the

appropriate norms of behaviour are for a person “like me.” Beyond just picking up on norms, by

the very act of communicating together in a like-minded group, group members better relate to

one another (p.22). Furthermore, the process of face-to-face interaction with members of a

small group is essentially catalyzing a process of identifying with larger-scale social groups that

this small group may represent. In Kramer’s work the “Old Timers” might be an example of a

smaller group, but they connect up to larger groups such as Ann Arborites, Michiganders,

Americans, Middle-Classers, and so forth.

The process of identity described above is also important given that people use these

identities in evaluating political information. In chapter 3 of Talking about Politics (Walsh, 2004)

gives some guidance here. In it, she explains that the greater the resonance between one’s

identity and the information conveyed, the more likely that information is to be received. In other

words, one’s identity acts as a reference point for judging whether or not new information should

be discounted. I see this as essentially the same as the receptivity axiom described by Zaller

(1992) and also akin to the motivated skepticism proposed by Lodge and Taber (2006). The

difference is that one’s social identity rather than prior beliefs represents the criteria for

acceptance or rejection of new information.

Social Interaction and the Media

Social interaction about politics between citizens does not happen in a vacuum. The

terms of engagement have already been set in large part by other actors. Ordinary citizens are

consumers of political information, but the table has already been set by elite discourse and

messaging (see Zaller, 1992; or Entman, 2003). Citizens mostly have the role of reacting to the

messaging they are receiving from elites, who are increasingly polarized from a partisan

standpoint

. This messaging is usually through the medium of news media, and

increasingly–partisan news media. While partisan news media has an effect of its own

(Dilliplane, 2014), it also continues to have an effect on interpersonal discussions and learning.

This is expressed in the two-step communication model of Druckman, Levendusky, and McLain

(2018). The basic idea is that those who watch partisan media are shaped by that discourse and

draw on the arguments they hear in the conversations of their everyday lives. So even if an

individual did not watch a particular piece of media, through exposure to the views of that media

as explained by a social contact, they are still essentially exposed to that media.

Druckman and colleagues tested this two-step model through lab experiments,

comparing attitudes and arguments about the Keystone XL pipeline after viewing 12 minutes of

either Fox or MSNBC (depending upon one’s partisanship). Some participants also engaged in

discussion groups after viewing the content, in both heterogenous and homogenous groups.

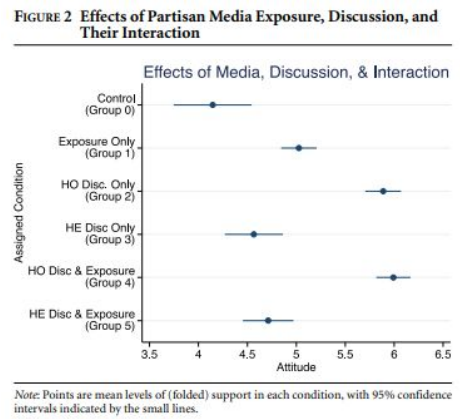

The result of each approach is shown in the figure below from p.105:

Stronger partisan attitudes are larger in this case, so moving right on the X-axis means

increasing partisan polarization. As you can see, exposure to partisan media does have an

effect, but the process of talking to one’s like-minded peers essentially doubles that effect. What

is it about talking to like-minded peers that is so powerful? Druckman et al. provide some

answers with their results. They find that participants in the homogenous groups rated

fellow-participants as 1.6 and 1.7 points more knowledgeable and trustworthy on a 7 point scale

than they rated participants in the heterogenous discussion group (p.109). Knowledge and

trustworthiness are the key ingredients for persuasion in the way Lupia and McCubbins (1998)

use the term. Learning from others requires persuasion, and that persuasion is much more likely

to come from homogenous groups.

At an even more fundamental level, everyone wants to feel intelligent because that

boosts self-esteem, the maximizing of which is one of the key drivers behind human behaviour

(see Hogg and Abrams, 1990). If you connect with a social group (which connection should be

fairly natural in a homogenous group) you identify with the other members; if they seem smart,

you’ll feel smart too. And together the group can reinforce feelings of well-being and self-worth.

This is as true of political groups as any other group. Self-reports of why people talk about

politics indicate that part of the reason is a desire to “enhance self-development [and] to gain

recognition” (Walsh, 2004, p.8 of Chapter 3). I take these as virtual synonyms for improved

self-esteem.

The opposite of what I describe above is true in heterogeneous groups. If participants in

those groups are saying things you don’t like or agree with, that feels bad because it implies you

hold the wrong positions. You may feel stupid, which I can attest is a very uncomfortable feeling.

One way to counter this feeling is to decide that those who hold contrary views are themselves

less intelligent and trustworthy. That is what the heterogenous group members in Druckman and

colleagues’ work appear to do.

Although they don’t touch on social identity, we might also imagine that the strength of

homogenous groups are also a result of the in-group identification process that Kramer

describes (Walsh, 2004). Since people consistently evaluate in-group members more positively

(see Marques et al., 1988), a homogenous group (which would include shared broader social

identities as well as the social identity of the small group itself) would also be evaluated more

favourably than a heterogenous group.

One takeaway from the findings visualized in figure 2 is that the heterogeneous

discussion groups in Druckman and colleagues’ work fared much better than homogenous

discussion groups in terms of polarization. If extended to the outside world, this would suggest

that heterogeneous social networks might reduce the current levels of polarization (at least

compared to if citizens only use homogenous social networks). Druckman et al.’s explanation

of the effect of these heterogeneous discussion groups is that they force “reflexive thinking,

perspective taking, and pressure to justify one’s opinion…the result is moderation of opinion

relative to those only exposed to partisan media” (2018, p.101).

How do we reconcile the findings presented above with Taber and Lodge’s work on

motivated reasoning among partisans (2006)? When reviewing the reasons Druckman et al.

give about heterogenous discussion groups, Taber and Lodge might respond that “pressure to

justify one’s opinion” will have the opposite effect to moderation of opinion–it will spur people to

invest more mental energy in justifying their original argument. Consider Taber and Lodge’s

findings from their experimental work. They found that when presented with both for and against

arguments, people exhibited greater partisanship partly because of exposure to the other side.

And this trend became even stronger for political sophisticates. People are motivated for various

reasons to accept information they agree with and reject information they disagree with (see

Zaller, 1992; Taber & Lodge, 2006; Kunda, 1990). This is the heart of motivated reasoning.

Which is what makes the results presented by Druckman et al. a little unexpected. According to

motivated reasoning, we should see an increase in polarization from exposure to dissonant

viewpoints (which is essentially what the heterogenous discussion group does). Could it have

something to do with the personal discomfort of disagreeing in person with strangers in an

experimental setting? People might hide their true feelings in such a scenario. In reality, we are

more likely to discuss political matters with people we know, rather than complete strangers,

and thus disagreement might feel a little more natural in this setting. Furthermore, the issue

used in their experiments (the Keystone XL pipeline) is obscure and technical enough that

participants may have felt shy about disagreement lest they reveal some glaring ignorance. In

real life, we are more likely to steer political conversation towards topics where we feel more

knowledgeable (like how much we dislike President Trump for example). A third aspect to

consider is the lack of a temporal dimension in Druckman et al.’s work (unlike Taber and

Lodge’s). As time passes, my expectation is that even those in heterogeneous discussion

groups will selectively remember only the points in favour of their argument and forget the points

opposed.

While Druckman and colleagues experiment is persuasive, it ignores how much of

political communication happens currently–through social media. How would the two-step

model fare on Facebook? Or Twitter? My belief is that it would hold up quite nicely, or indeed

show even greater effects. Let me put myself in the shoes of a typical citizen in my home state

of Utah as an illustration. After waking up this morning, and while making my (decaf) coffee, I

happen to glance at the curated headlines on my phone which are provided to me by Google

based upon my previous activity. Today I see a story about Hunter Biden’s recovered hard-drive

in all its unsavoury details from the New York Post. I quickly share the article on Facebook with

my own comment attached: “Biden is so corrupt!!!.” Now my close friends and family can read

the article if they want, but more importantly, they can see how I feel about the article.

Presumably these social media friends like and respect me (otherwise why would they follow my

feed?), and if they also share my political affiliations, they can both simultaneously adopt my

views, read the article themselves, and re-share it. So rather than providing the “double dose” of

partisanship that Druckman et al (2018) mentioned, this is almost a triple dose because the act

of re-sharing probably means you are mentally preparing to defend it online as well. And if

enough people re-share the story, it creates what Munger (2020) calls a credibility cascade,

where enough social recommendations about a political story can attach a veneer of credibility

to stories that otherwise would not appear very credible.

Carlson (2019) provides replication ‘with a twist’ of Druckman et al’s two-step model

through a couple of experiments. In the first, he asks participants to convey information about a

news story (in writing) to an unknown Democrat, Republican, or Independent. From that

experiment (see p.330-332), he finds that people tend to write less information than what was

presented in the news article. Furthermore, they usually differed in terms of content and tone.

Basically, ordinary people were generally worse at conveying information than news stories are.

And then in the second experiment, subjects were exposed to the written communications from

the first experiment to see how much they could learn from them when compared to being

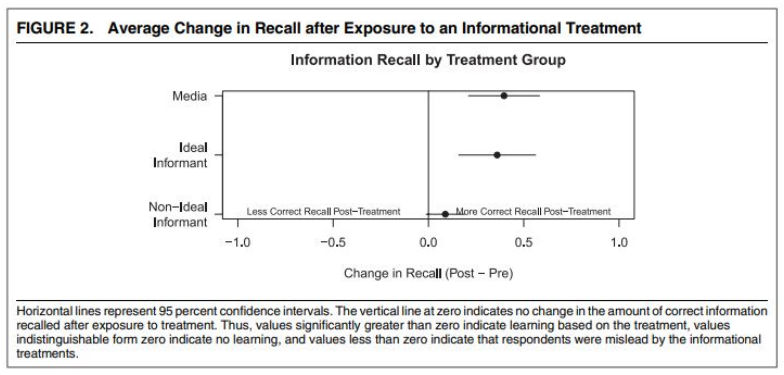

exposed to the original article. Their results are shown in the figure below (p.335). The caption

“Ideal Informant” means someone who shares the same partisan identity and is more

knowledgeable than the recipient (p.334).

What I like about this figure is its elegance in showing the dual nature of learning from

social interaction. It depends entirely upon who we are learning from. We can learn nearly as

well from a trustworthy source as we can from viewing the media story ourselves. Conversely,

an untrustworthy source leads to ignorance and errors. Carlson here is basically recreating

Lupia and McCubbins’s findings on persuasion only occurring when a person views the source

as being knowledgeable and sharing common interests (1998, p.40). The common interests in

this case would be represented by a shared partisan identity. Like Druckman and colleagues,

Carlson also does not address social identities, but we might imagine that his ideal informant is

partly “ideal” in the mind of the individual who is using that informant because of a shared social

identity (or a perceived shared social identity).

Although Carlson does not advance beyond the two-step model of media effects in his

2019 article, in an earlier paper (2018), he goes one step further. In that paper, he essentially

runs the same experiment, but with 3 participants. So a participant views a news story, writes it

down, and passes it on. And then the next person views that story from the first person and

does the same thing. And so on with the third person. With each succeeding step, the amount of

information decreases (see figure below from p.351) and the number of distortions increases by

about a quarter (p.350).

Anyone who has played the game “broken down telephone” as a child can attest to this

finding. If you’re unfamiliar with the game, here’s how it works: one person thinks of a phrase

and then whispers it into the ear of the person next to them, who then whispers it into the ear of

the next person, and so on down the line. By the time the last person repeats the phrase it is

nearly always completely garbled and changed from the original phrase. If I had known

someone was going to use the game to publish academically, I certainly would have taken

better notes all those years ago!

In fact, I found myself reflecting on “broken down telephone” after reading both Carlson

pieces, and I think there would be merit in recreating his experiment with more fidelity to the

original game. That is, verbal instead of written. In face to face social networks, communication

is verbal which probably leads to even greater losses of information and more opportunity for

distortion than written communication. I’m thinking of the countless times I’ve started to tell my wife Bethan about an interesting political science article I’ve just read only to realize that I can only

remember maybe the thesis and a couple of the more compelling anecdotes. I did that just the

other day with the Lodge and Taber (2006) piece on motivated reasoning. All I could think of

was just that–that they talked about motivated reasoning, and the experiment they ran to test it.

Her understanding of the Lodge and Taber article is obviously going to be more limited than if

she had read the article, despite my being (ostensibly) a trustworthy source of information for

her (in the Lupia and McCubbins sense). In other words, despite my being presumably an “ideal

informant”, I was not able to facilitate learning like Carlson would expect from me. If on the other

hand, I were able to share a written account of Lodge and Taber’s piece after reading it, I

doubtless would have been more informative. Writing is costly effort–it requires more serious

attention and cognitive focus. The point I’m making here, if it is unclear, is that I think there is a

discrepancy between learning through social networks that occurs verbally and that occurs

through written communication.

That’s not to say that I disagree with Carlson’s assessment. Indeed, his approach might

be incredibly useful given the fact that most social media communication (besides videos and

pictures) is written. People are exposed to political posts written by their friends and family, who

may be reacting to the latest news from a more traditional media source. They react to the

information, someone else reshares their reaction, and so the game of broken telephone goes

on, with each link resulting in greater distortion.

Social Interaction and Democracy

Even if we accepted Druckman et al.’s findings about reduced polarization through

heterogenous discussion groups when compared to homogeneous discussion groups, these

heterogeneous groups may not exist for most citizens. Kramer tells us that when people talk

about politics, it is usually to those they are already firm social contacts with, such as family

members and coworkers (Walsh, 2004, p.22). And we know from Diana Mutz’s work, that

cross-cutting interpersonal networks are the exception rather than the norm (2001). Mutz’s

solution to the lack of interpersonal political cross-cutting information is relying on the media to

expose citizens to dissonant views. Unfortunately, as discussed in Prior (2005), the greater

access to more entertainment options has led to less news-watching by ordinary citizens, and

thus less exposure to contrary views.

If we’re getting less heterogeneous discussion groups, and hence less cross-cutting

views, that means by definition that we’re getting more homogenous groups. Although that may

be more comforting for individual citizens psychologically, the literature I have reviewed in this

essay suggests that will lead unerringly towards greater polarization. It is also fundamentally at

odds with the notion of deliberative democracy. There can be no real deliberation if we are only

comfortable deliberating within our own groups, or discounting contrary information by definition

of its contrary sourcing. In the deliberative or republican flavours of democracy, the best

argument is supposed to win, and that happens through bottom-up discussions between

citizens of differing views. The findings discussed in this essay about citizens’ interpersonal

communication strategies do not bode well for that viewpoint.

Another potential source of concern for democracy, if we rely upon a foundation of citizen

discursiveness, is citizens’ tendency to believe and perpetuate false information and conspiracy

theories (see Oliver & Wood, 2014). This trend is likely to increase if citizens rely upon each

other as political information sources. Unlike standard news media, information gained from

one’s peers has no fact-checking. Information spread can be biased and “wildly inaccurate” from

one’s social network (Carlson, 2019, p.326). This is especially true on social media, where the

credibility cascades gained by multiple shares through one’s trusted peer network give even the

most implausible stories a quick coating of credibility. We are seeing this phenomenon in action

already, as people rely more heavily upon their social media for political information.

Movements like QAnon are good examples of this trend.

It is as Carlson concludes: “social information is not a panacea” for solving the problem

of an uninformed electorate in a democracy (2019, p.338). Yes, learning can occur from ideal

informants, but that presupposes that everyone has ideal informants handy in moments of

political decision-making. Worse even than a lack of access to ideal informants is the tendency

of people to mislabel their social contacts as ideal informants. Carlson claims that people both

routinely over-estimate the expertise of their social ties, and when they do have those ties, they

avoid them to minimize “psychological discomfort” (p.338). These ideal informants are a bit like

Ahab’s white whale: rare and frightening.

As I discussed in this essay, however, there is hope for democracy if we change

our conception of what democracy looks like. That is, if we abandon our insistence that

democracy should represent the republican or discursive democracy proposed by progressive

era philosophers. Indeed, when I read the 2-step model put forward by Druckman, Levendusky,

and McClain (2018), I immediately thought of its applicability to liberal pluralist democracy. As

Baker describes it, liberal pluralism is the recognition that each person has his or her own

interests to pursue, interests that can be achieved through reliance on a group of like-minded

individuals who band together to gain political power. Each person already knows what is in

their best self-interest, they don’t need discursive, bottom-up discussions to find out the public

will (as in republican democracy); they just need an attachment to a group that will press their

interests. And yes, that will conflict with other people’s interests, but that is what democratic

politics is all about–competition over whose interests will be represented. Democratic elections

provide the mechanism for healthy expression of this conflict. It is through the bargaining and

compromises that happens when groups of self-interested individuals form larger groups

capable of achieving electoral power that is the crux of democracy. As long as there are fair

rules of competition, competing groups of self-serving, like-minded citizens can ensure that at

least the majority of the populace gets the policy outcomes they want. And if we adopt this view

of democracy, we also need not be concerned about citizen incompetence or polarization.

Citizens just need to know enough about each party to know which one represents more of their

interests, and in terms of polarization–in liberal pluralism that is not a negative, it is the norm.

I leave it to the reader to decide on the normative implications of embracing such a

model. For my own part, I feel somewhat uncomfortable with such a model of democracy, but it

is undoubtedly a more accurate model to describe the current political system in the United

States. In terms of the 2-step model discussed in this paper, it fits nicely with that theory. The

political elite and media disseminate information, which is picked up by some citizens who

transfer that information to other citizens. Although partisanship may increase as a result, that is

expected in liberal pluralism. Within this system, it is highly useful to have citizens disseminating

information gained from elites to one another.

Cramer’s findings about social identity fit a liberal pluralist model too. Social groups with

which one finds identity are the perfect springboard for coalescing into larger groups that

compete for political power. We see this all around us. For example, a Black social identity is a

useful tool for the Democratic party to know how to distribute social benefits when in power. An

Evangelical social identity does the same thing for Republicans. The social identities are just

another way of forming groups that compete for political power.

Works Cited

Baker, C.E. (2002). Media, Markets, and Democracy. Cambridge University Press.

Carlson, Taylor N. 2018. “Modeling Political Information Transmission as a Game of Telephone.”

The Journal of Politics 80(1).

Carlson, Taylor N. 2019. “Through the Grapevine: Informational Consequences of Interpersonal

Political Communication.” American Political Science Review 113: 325-39.

Dilliplane, S. (2014). Activation, conversion, or reinforcement? The impact of partisan news

exposure on vote choice. American Journal of Political Science, 58(1), 79-94.

Druckman, Levendusky, and McClain. 2018. “No Need to Watch: How the Effects of Partisan

Media Can Spread via Interpersonal Discussions.” American Journal of Political Science 62:

99-112.

Entman, Robert M. 2003. “Cascading Activation: Contesting the White House’s Frame After

9/11.” Political Communication 20(4): 415–32.

Hogg, M. A., & Abrams, D. (1990). Social motivation, self-esteem and social identity. In D.

Abrams & M. A. Hogg (Eds.), Social identity theory: Constructive and critical advances (pp.

28-47). New York: Harvester Wheatsheaf.

Kunda, Z. (1990). The case for motivated reasoning. Psychological bulletin, 108 3, 480-98.

Lupia, Arthur & Mccubbins, Mathew. (1998). The Democratic Dilemma: Can Citizens Learn What

They Need to Know? Cambridge University Press.

Marques, J. M., Yzerbyt, V. Y., & Leyens, J. (1988). The black sheep effect?: Extremity of

judgments towards ingroup members as a function of group identification. European Journal of

Social Psychology, 18(1), 1-16. doi:10.1002/ejsp.2420180102

Mutz, Diana C. 2001. “Facilitating Communication across Lines of Political Difference: The Role

of Mass Media.” American Political Science Review 95(1): 97–114.

Oliver, J. E., & Wood, T. J. (2014). Conspiracy theories and the paranoid style (s) of mass

opinion. American Journal of Political Science, 58(4), 952-966.

Prior, Markus. 2005. “News vs. Entertainment: How Increasing Media Choice Widens Gaps in

Political Knowledge and Turnout.” American Journal of Political Science 49: 577-92.

Taber, C. S., & Lodge, M. (2006). Motivated Skepticism in the Evaluation of Political Beliefs.

American Journal of Political Science, 50 (3), 755-769.

Walsh, Katherine. 2004. Talking about Politics: Informal Groups and Social Identity in American

Life. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Zaller, J. (1992). The Nature and Origins of Mass Opinion (Cambridge Studies in Public Opinion

and Political Psychology). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

doi:10.1017/CBO9780511818691

Social Interaction as a Political Phenomenon

In order to navigate the political world and make decisions that benefit them, human beings need to be able to learn about politics. They can either do this themselves through experience, or rely upon the knowledge others are ready to impart (Lupia & McCubbins, 1998). This knowledge can come from political elites, the media, or (as is the focus of this paper) one’s social network. Since human beings are cognitive misers, they want to learn the information they need with the least effort possible (see chapter 2 of Lupia & McCubbins, 1998). One’s social network, therefore, represents an easy means of acquiring political information with little costly effort (Carlson, , 2019, p.325). Someone else has already done the hard part (i.e. reading about political events); you can just benefit from their efforts. This represents the rational citizen that Anthony Downs would approve of, and would appear to be only a theoretical construct of a citizen, but for focus group work that has revealed that people do indeed profess to talk about politics in order to gain information as well as persuade others (see Walsh, 2004, chapter 3).

Whenever we communicate socially there is always the intervening effect of social identities to consider. Cathy Kramer (referred to in the citations for this paper as Walsh, 2004) and her study of the “old timers” provide most of the work here. Kramer found that when discussing things in social groups, participants repeatedly use collective identities in how they frame issues (p.10). Their social identities are also a key part in how they evaluate issues. Kramer gives a good account of this process and how it operates on p.19. She explains that through social interaction, people evaluate themselves in comparison with the other individuals in the group and the norms they display. This gives them an idea of what they perceive the appropriate norms of behaviour are for a person “like me.” Beyond just picking up on norms, by the very act of communicating together in a like-minded group, group members better relate to one another (p.22). Furthermore, the process of face-to-face interaction with members of a small group is essentially catalyzing a process of identifying with larger-scale social groups that this small group may represent. In Kramer’s work the “Old Timers” might be an example of a smaller group, but they connect up to larger groups such as Ann Arborites, Michiganders, Americans, Middle-Classers, and so forth.

The process of identity described above is also important given that people use these identities in evaluating political information. In chapter 3 of Talking about Politics (Walsh, 2004) gives some guidance here. In it, she explains that the greater the resonance between one’s identity and the information conveyed, the more likely that information is to be received. In other words, one’s identity acts as a reference point for judging whether or not new information should be discounted. I see this as essentially the same as the receptivity axiom described by Zaller (1992) and also akin to the motivated skepticism proposed by Lodge and Taber (2006). The difference is that one’s social identity rather than prior beliefs represents the criteria for acceptance or rejection of new information.